Last week, my interest was piqued by an article from Piecework that led me down the kind of rabbit hole I particularly like – the kind that involves a complicated but exciting era in US and world history, and that also involves the development (or non-development, depending on the events) of needlework and the needlework industry.

The Industrial Era was a crazy time in history, really, full of contradictions. Every era of history is easier to evaluate retrospectively, of course. While it is obvious that many good things sprang from the Industrial Era, or took root during that era, it was yet an era fraught with abjectly dismal circumstances and consequences in many regards.

Today, needleworkers in the US who want to work with silk obtain silk threads as imported goods. We don’t manufacture silk in the US.

During the Industrial Age, however – from the early 1800’s well into the first half of the 20th century – we actually had mills that produced embroidery silk that was popular around the world.

Initially, the silk was produced from worm to fiber, but that didn’t last long. Eventually, with the opening of Japan for trade, it made more sense to import the raw silk from Japan, where centuries of breeding and raising silk worms had already established a flourishing industry producing the best quality silk. The silk was then finished in the US into various textile-related products.

The brand of silk produced in America that was most popular and that developed and grew during this era was Corticelli, produced in Florence, Massachusetts.

The name Florence, in fact, was a marketing ruse. The mills that eventually produced the famous brand (named Corticelli to play off the “Florence” connection) were actually in Northampton, Massachusetts. The mill area was renamed Florence simply to imply a connection to Italy as an appeal to the oh-so-cosmopolitan sensibilities of the American consumer.

Funny how marketing works, isn’t it?

So, don’t be fooled by the name Corticelli or the name Florence – neither had any direct connection with Italy, except to borrow Italy’s laurels to entice consumers to buy.

Things rather fell apart for the Corticelli brand by the early 1930’s, with the Depression and, not long after, the second World War. The thread-making industry in the US never really recovered, and the availability of silk was relegated primarily to imports.

Of course, there’s much more to the history of silk production during this era – and the production of many things in the industrialized Northeast. It takes some interest in the specific historical era to really delve into the nitty gritty details, which really aren’t part of a needlework blog!

A Good Article!

But if you do have interest in reading particularly about the production of silk threads and the history of Corticelli silk, take a look at this article from Pieceworks that came out last week. It is well researched and enjoyable to read.

Then, if you decide to go further into the era, be warned! You may end up touring coal mines in Pennsylvania, visiting the sites of historical innovation and historical disasters all over the northeast, and your view of industrialization might end up a little less sunny than that implied by the cute kitten advertisements of Corticelli.

They are pretty cute advertisements! I wonder if anyone has ever embroidered any of them?

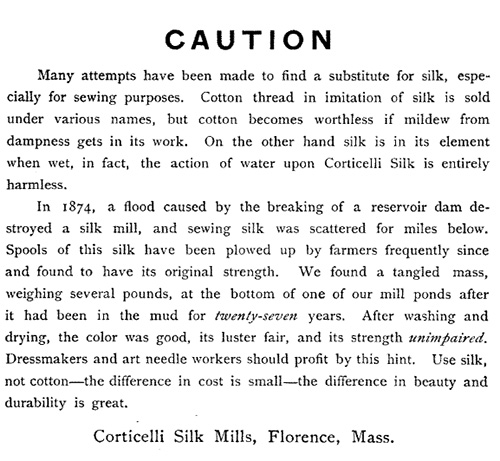

This advertisement, though, is less appealing, in my mind, and it speaks to the contradictions of the era mentioned above:

That advertisement always makes me a bit sick when I come across it in the old Corticelli-related booklets.

Presented as a “warning” not to use any substitutes for silk, anecdotally, it tells the consumer that, after a dam above a silk mill burst back in 1874, twenty-seven years later, silk found in the leftover muck was still as strong and usable as ever.

Therefore, buy Corticelli!

What the advertisement fails to mention is that the dam that burst during the Mill River Flood of 1874 did so because of the lack of oversight by the mill owners (who also owned and built the dam) to ensure that the dam was, in fact, sound. Eight years of leakage and many years of concern from the people who lived in the valley and worked at the mills didn’t result in any measures to fortify the dam, which flooded the valley in 1874, killing many, ruining industry and livelihoods, and wiping out towns.

I always find it mind-boggling that they used the event as an advertisement for the quality of their silk.

You can read about the Mill River Flood here. There’s also an article by the New England historical society about the flood here. The latter article is not the best, perhaps, but it gives some background.

If this era sparks your interest and you like history and non-fiction, one of the more recent books I listened to on Audible (great to do while stitching!) was The Johnstown Flood by David McCullough. That particular flood, which took place in 1889, in Pennsylvania, had to do with the steel and railroad industries, but it is riveting history.

And if you’re ever in the area slightly to the east of Pittsburgh, the Johnstown National Memorial operated by the National Park Service is worth a visit. Situated in a beautiful area of Pennsylvania, the memorial (and grounds) is well-presented and maintained, easily manageable, and tells a compelling story.

Piecework

Piecework Magazine is more of a general needlework magazine. It occasionally has embroidery-related content, but it also focuses on knitting, lace-making, and other needlework and textile-related topics. While I occasionally enjoy the magazine, the range of topics is often too wide to hold my interest all the time. If your textile interests focus solely on embroidery, it might be too broad. But their newsletter is free.

So if you haven’t already done so, you might sign up for the Piecework newsletter, which you can do on their website. Quite often, their articles are excellent little gems.

I hope you enjoy looking into this one about the production of silk threads in America and the rise of a world-wide popular brand of silk called Corticelli.